Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches.

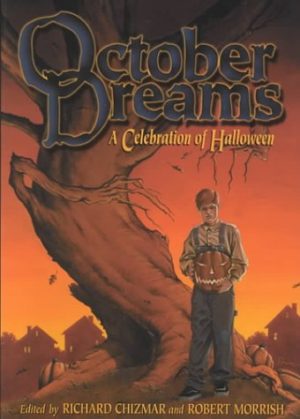

This week, we cover Caitlin R. Kiernan’s “A Redress for Andromeda,” first published Richard Chizmar and Robert Morrish’s 2000 October Dreams: A Celebration of Halloween anthology. You can find it more easily in The Weird. Spoilers ahead.

“Ahmed and the woman with the conch-shell tattoo lean in close and whisper the names of deep-sea things in her ears, a rushed and bathypelagic litany of fish and jellies, squid and the translucent larvae of shrimp and crabs.”

Marine biologist Tara finds Darren’s face more honest than handsome. Maybe that’s why she’s attracted to him—and why she’s accepted his invitation to a Halloween party at an isolated house north of Monterey. It’s no masquerade, Darren’s assured her: just come as yourself.

The Dandridge House perches on a headland above the Pacific, amid tall grass wind-whipped, like the sea, into waves and fleeting troughs. With its turrets, high gables, and lightning rods, it would scream Halloween even without scores of candle-lit jack-o’-lanterns outside. A black-haired woman is waiting on the porch. The jack-o’lanterns, she says, were carved by the guests: one hundred eleven for each year the house has stood. But it’s getting late, come inside.

Darren introduces Tara as the marine biologist he’s been telling everyone about. The other guests wear impeccable black; in her white dress Tara feels like “a pigeon dropped into a flock of crows.” A Frenchwoman with kelp-brown nails tells Tara it’s always nice to see a new face, especially one as “splendid” as hers. A fat man in a storm-gray ascot is happy to learn she’s a scientist. They’ve had so few of those.

As Darren draws her aside, Tara notices how shabby the rooms are. There’s little furniture. Windows are drapeless, and velvet wallpaper peels from the walls like reptile skin. Candles and gas fixtures, not electricity, provide flickering light. Darren reassures her that the partygoers are a tight-knit group, probably as anxious about her coming as she is about meeting them. They don’t mean to be pushy with their questions, and she doesn’t have to answer. They’re just impatient. Impatient about what, Tara would like to know, but Darren leads her back to the crows.

A string quartet plays. The fat man introduces himself as Ahmed Peterson. Learning Tara’s particular field is ichthyology, he talks about his friend thinking a stranded oarfish was a sea serpent. She tops him with her own story about seeing a live oarfish twenty feet long. A woman rings a brass gong, and the guests file from the parlor to the back of the house. Darren gives Tara a coin, which she’ll need later. She assumes they’re going to play a party game.

A door opens onto winding, slippery stairs cut into the rock. Damp walls gleam in the light of the guests’ candles and oil-lamps. Cool air gusts from below, carrying the salt-smell of the sea and a less pleasant fishy odor. When Tara asks where the hell they’re going, a woman with a conch shell tattooed on her forehead looks disapproving, and Darren only responds, “You’ll see. No one ever understands at first.” He grips her wrist too tightly, but before Tara can protest, she sees the sea-cave at the bottom of the stairs.

A warped boardwalk hugs the cave walls, above a deep pool welling chartreuse light. The crows take their places as if they’ve been there hundreds of times. Darren, ignoring her pleas to leave, looks like he’s witnessing a miracle. The crows part so she can see the stones jutting from the middle of the pool, and the thing chained there.

Tara’s consciousness splits between herself in the sea-cave and herself apparently later, lying in the tall grass with Darren. The chained thing was once a woman. Now she has spines and scales and podia sprouting from her distended belly. Crimson tentacles dangle between her thighs; barnacles encrust her legs; her lips move soundlessly as she strains against her corroded shackles. All the others have dropped their coins into the pool. Tara clutches hers like a tether to the known world.

“She keeps the balance,” Darren says. “She stands between the worlds. She watches all the gates.” But does she have a choice, Tara asks. Do saints ever have choices, Darren counters. Tara can’t remember. Ahmed and the tattooed woman whisper the names of sea creatures in her ears, too fast. Somehow they become the Mock-Turtle and Gryphon from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and sing snatches from “The Lobster Quadrille,” while Darren explains that the jack-o’-lanterns are a sort of lighthouse beacon: those who are rising, who rise every year, need to know that the partygoers are watching. The number of watchers is fixed. One of them has been lost. Tara must take their place by dropping her coin into the pool by midnight.

Buy the Book

Summer Sons

She sees those who rise in the glowing pool, all coils and lashing fins. She drops her coin and watches it sink, “taking a living part of her down with it, drowning some speck of her soul.” Like the chained woman, like the crows, she too now holds back the sea.

I told them you were strong, Darren whispers to Tara, above, in the grass. Below on the boardwalk, the crows dance. The chained woman slips into “a stinging anemone-choked crevice on her island.”

Tara wakes in the grass on the headland. Cold rain falls. Below the house, breakers roar. She can’t remember climbing from the sea-cave. Darren and the crows have driven off. The house is dark, all the pumpkin beacons gone.

Next year, Tara knows, she’ll come a week early and help carve the jack-o’-lanterns. She’ll wear black. She’ll know to drop her coin in the pool quickly, and quickly turn away.

A gull seizes something dark and wriggling from the seething sea. Tara wipes rain or tears from her eyes and starts down the sandy road to her car.

What’s Cyclopean: The house abuts the “unsleeping, omnivorous Pacific,” a phrase that only gets more disturbing and delightful the longer you think about it.

The Degenerate Dutch: Tara prefers the small group at the isolated house to New York’s Halloween parties, gaudy with noisy drunks and drag queens.

Weirdbuilding: This week’s story is reminiscent of “The Festival,” and yet another entry in the long litany of oceanic weirdness.

Libronomicon: The lines about getting thrown with the lobsters out to sea, which might easily seem like the secret nightmare verse from “Octopus’s Garden,” are actually from the Mock Turtle’s Song in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland—little surprise, then, that they’re shortly followed by an influx of imagery from the Mad Hatter’s tea party.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Do quotes from the Mad Hatter count?

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Word of warning: when your new boyfriend invites you to an isolated party with a close-knit, strangely-mannered group of friends who accept only one new member at a time, and none of the previous new members are in evidence… the fact that dude looks honest may not keep you safe. Things actually turn out much better for Tara than I was anticipating. And that’s kind of awesome, because what happens—to the degree I can tell what happens at all—is much weirder and more interesting than anything I was bracing for.

Kiernan’s very good at riffing on Lovecraft stories. Previously we’ve encountered a close sequel to “Pickman’s Model” and a distant play on “Call of Cthulhu.” This week’s story seems like a thematic echo of “The Festival,” in which our narrator gets invited to a strange bioluminescent ceremony in the bowels of a house, and wakes up alone and unsure of the level of reality of anything they’ve encountered. “A Redress for Andromeda” goes beyond the Lovecraft, though: the ceremony in question is more resonant, and the narrator ultimately acquiesces to participation rather than running away. There’s wonder and glory here, and a willingness to pay something that—the story suggests—we owe.

Exactly what’s owed, and what the ceremony accomplishes, are left obfuscated. The closest we come is a description of what the saint/sea monster/woman is doing down there: keeping the balance, standing between worlds, watching the gates. We also learn that something rises, and expects to see the jack-o-lanterns as proof that we’re paying attention—and that the dropped coins are a sacrifice of more than metal, that they hold back the sea with pieces of soul.

The title provides a framework on which to hang some of these hints. Andromeda, of course, was offered as sacrifice to Poseidon’s sea serpent to protect the land from his wrath, and rescued by Perseus. So is the “redress” owed to Andromeda, for her near-sacrifice? Or is it owed to the sea, for her survival? Or both? The ceremony honors the sea monster saint, but also sacrifices to the sea—or something in it. Unsleeping, omnivorous… it’s not the Dreaming God of R’lyeh, anyway, who both sleeps and has distinctive appetites.

Tara, an ichthyologist, might bring to the ceremony a more scientific awareness of the ocean’s dangers—which is not necessarily a more comforting perspective. “The angry sea, the cheated sea that wants to drown all the land again” can get what it wants via the intervention of gods, or just by waiting on human self-sabotage. “Bright Crown of Glory,” Livia Llewelyn’s story from a few weeks back, suggests that these two routes to sea level rise may not be so distinct.

So what is the world’s shame, down in that subterranean tide pool, that convinces Tara to drop her coin and join the crows for the long haul? What would have happened if she’d refused? We never do get an answer to the question of whether saints have choices, and it’s just as unclear whether Tara does. There’s something in the hallucinatory Lewisian mid-point of the ceremony—danger and fear and silliness all mixed together, an eldritch ceremony carried out by pumpkin-light—to draw us in, and draw us to return, even without any promise of answers.

Anne’s Commentary

It’s reasonable that the Andromeda of Classical mythology would appeal to Caitlin Kiernan. They (the author’s preferred pronoun) are a paleontologist with a special interest in the mosasaurs, giant marine reptiles of the Late Cretaceous. Artists’ renderings show something like a shark-lizard hybrid. Not a cute little gecko of a lizard—think Komodo dragon crossed with saltwater crocodile. Make it ten meters long and you’ve got a respectable sea monster—that is, Andromeda’s would-be devourer.

Andromeda’s parents were Cepheus and Cassiopeia, rulers of ancient Ethiopia. Cassiopeia bragged that Andromeda was more beautiful than Poseidon’s sea nymphs, maternal hubris that pissed him off big time. Showing the usual godly restraint, Poseidon flooded the Ethiopian coast and tasked his pet mosasaur Cetus with devouring any Ethiopian who dared go back in the water. An oracle told Cepheus that to restore the value of oceanfront property he’d have to sacrifice Andromeda to Cetus. So Cepheus did the politically expedient thing and chained Andromeda to a seaside rock, an irresistible snack for any monster.

Luckily for Andromeda, Perseus slew Cetus before the beast could even nibble on her comely toes. Perseus then made her his queen, and they had lots of kids and eventually became constellations, as people in Classical mythology tend to do.

Kiernan’s rock-bound lady gets no happy ending. Instead she gets to be a saint. Many Catholic saints are martyrs, suffering gruesome tortures before their redress of heavenly bliss. Temporary agony for eternal ecstasy sounds like a good deal. But eternal agony for temporary relief? If there ever is relief for Kiernan’s lady. Tara doubts it, but as Darren says, no one ever understands at first.

I don’t understand at last. Which is fine?

“A Redress for Andromeda” opens like a conventional horror story. You have your decaying, isolated manse and an ominous calendar date: Halloween, complete with jack-o’-lanterns. The house has been a resort of animal-sacrificing occultists. The protagonist is an occult-innocent, lured to the house under the pretext of a low-key Halloween party. All the other “party-goers” dress in black and are a tight-knit bunch, like any respectable coven. Whereas Tara is dressed in prim white, like any respectable virgin sacrifice. Everyone but Tara anticipates an unexplained Event. The Event will involve odd silver tokens, which makes Tara think party game. Any respectable reader knows the Event will be no game.

As midnight approaches, things take a Lovecraftian turn. The party files down a stairway “cut directly into the native rock.” Any such stairway can lead to nothing good. Especially when the walls are damp, the steps slippery. Especially when the air smells like “bladderwrack and dying starfish trapped in stagnant tidal pools.” And most especially when an eerie yellow-green light begins to illuminate the descent. The stairway ends in a sea-cave pool featuring a rocky island with—a thing chained to it. The thing is unnameable, indescribable—at least, Kiernan doesn’t name or describe it right away.

Section break. Now the weirdness escalates not so much in what happens as in how Kiernan structures their narrative. As if her drinks were spiked with strange brew, Tara’s consciousness splits between the sea cave and the grassy meadow, between recent story past and story present. In their online journal, Kiernan remarks: “I have no real interest in plot. Atmosphere, mood, language, character, theme, etc., that’s the stuff that fascinates me. Ulysses should have freed writers from plot.” And there is something Joycean in this section’s spatial and temporal disjunctures; its apropos-of-what conversations; its giddy plunge into Alice’s Wonderland as Peterson becomes Carroll’s Mock-Turtle and the tattooed woman his Gryphon. The two murmur an incantatory list of deep-sea fish and invertebrate genus names in Tara’s ears; they follow up with the Mock-Turtle’s song, “The Lobster Quadrille.”

Interwoven with this phantasmagoric language-play is “the plot”: The marine-life/human hybrid chained to the rock is revealed as a suffering saint who stands between worlds and watches the gates; Deepish Ones rise, all coils and lashing fins; Darren urges Tara to drop her coin into the pool and become a redress-bringing watcher; Tara surrenders bits of life and soul to seal her acceptance of the responsibility.

We still don’t know how “Andromeda” ended up in a sea-cave north of Monterey, or how she balances Everything, or what the Risers are, or how the coin-tokens serve as redress. Again, do we have to?

In the final section, Kiernan returns to conventional narrative. Pelted with cold rain, Tara wakes to the “real” world where practical things matter, like her purse and where she parked her rental car. She makes what sense she can of her experience, projecting the bitterness of its secrets on the again-deserted house and planning to come early next Halloween week to help carve jack-o’-lanterns.

Then she watches a gull snatch squirming mystery from the sea, and atmosphere and emotion close the tale.

Next week we continue on the track of a nasty tome in Chapter 2 of John Connolly’s Fractured Atlas.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her short story collection, Imperfect Commentaries, is available from Lethe Press. You can find some of her fiction, weird and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.